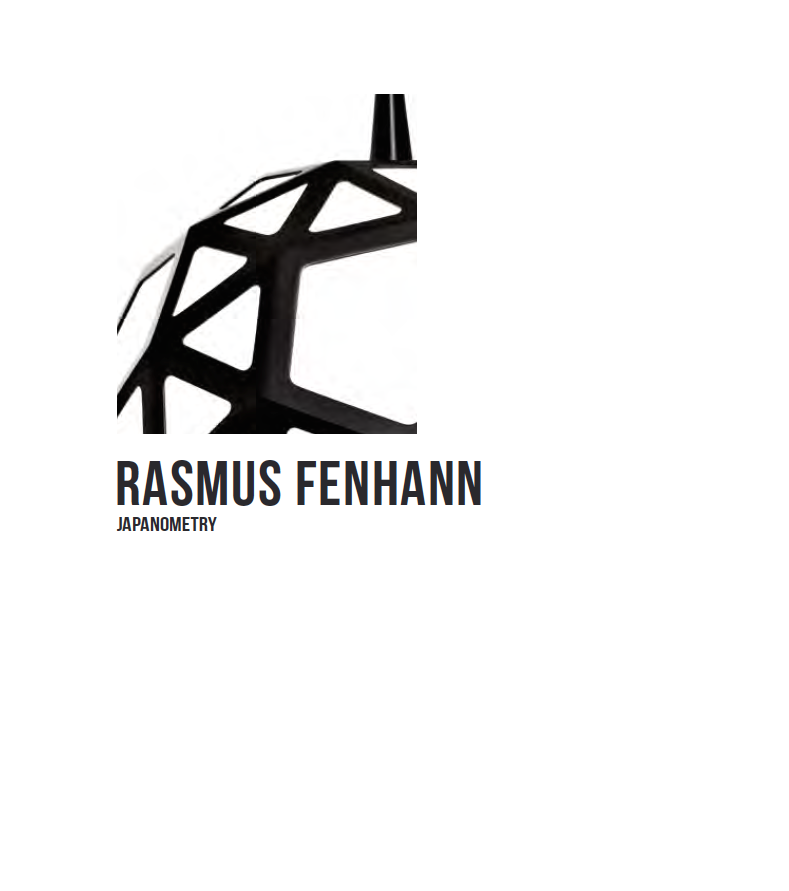

With Japanometry, the Danish designer and master cabinetmaker Rasmus Fenhann proposes a signature exhibition exploring the meanders of pure geometrical form through origami-inspired wood constructions. Danish by birth but with a Japanese soul, Rasmus Fenhann invented the clever neologism Japanometry to evoke his two major inspirations, Japan and geometry. Visually and linguistically, this exhibition seems like a kind of statement. Ten new works in wood, mostly lamps and tables characterized as design-sculptures, are conceived specifically for the exhibition at Galerie Maria Wettergren. Lightweight and rather small in scale, their crystalline shapes are remarkable through their combination of Japanese Zen and mathematical beauty.

It has to do with being able to zoom in, infinitely, Fenhann says. There mustn’t be any flaws, not even the tiniest, in the delicate woodwork of a great Japanese master cabinetmaker. Time is key, and infinite repetition is expected until a level of breath-taking perfection is reached. In Japan, significant cabinetmakers are not expected to be like ordinary human beings. It’s impossible to have a family life and do ordinary everyday tasks, since you have to be completely dedicated and devote your entire life to this Zen principle, Fenhann says. He knows from close-hand experience, as he himself have gone through several apprenticeships in the workshops of Japanese master cabinetmakers, such as Kohseki, during his travels in Japan in 2001 and 2003.

Indeed, to a large degree Fenhann’s work represents the aristocratic quality of delicate handmade cabinetmaking expressed by the Japanese term Sashimono (指物). His work is guided by the same principles of simplicity, repetition and respect for wood as a living material. His painstakingly precise treatment of wood surfaces, ending up in a velvet-like, soft finish and with invisible joints, is the result of an extraordinary effort, which is both mental and physical. It is absolutely exquisite, close to obsessive. In the Japanese aesthetic tradition, unlike the European, there is no separation between the work of the mind and the hand. The fact that Fenhann rejects the idea of an assistant and produces all his pieces himself in small limited editions can be seen in this holistic perspective. He does not work with the industry either. As the hand and the mind form a single spiritual bond, there is a kind of unique and non-transmittable type of work at stake here.

However, this does not prevent him from using high-technological devises such as the CNC (Computerized Numerical Controle) and CAD (Computer Aided Design) machines. The majority of his complex geometrical forms are designed by computer, and part of his works is CNC-cut. This is perhaps one of the most significant characteristics of Fenhann’s work, and also quite an achievement, since the two worlds of craft and industry are generally rather suspicious towards each other. Having the Japanese spirit and skills under his skin, he simultaneously manages to break free from the restrictions of pure craftsmanship by exploring the high-technological means of manufacturing in the present day. For him, the connecting link is the natural geometrical forms such as those observed in crystals. The perfect beauty of mathematical harmonies has certainly fascinated humankind since Antiquity, but our computer age is particularly capable of unfolding the infinite richness of nature before our eyes, just like an origami. Indeed, by zooming in and by modulation, Fenhann transforms complex geometrical principles into stunning sculptural forms.

The polyhedron is his absolute favourite, as it is the most harmonious and resistant of all geometrical forms. The origami-inspired “Hikari lamps” (“Hikari” means light in Japanese) are all polyhedrons constructed of almost paper-thin Oregon pine veneer only 1.8 mm thick. The first Hikari lamps were made in 2004, and the following year the Danish Designmuseum opened a solo exhibition for these works, entitled Aero. Since then, Fenhann has been developing complex variations of these lamps as well as the lightweight table-sculpture “Kubo” from 2007.

It might be interesting to note that both the “Hikari” and the “Kubo” are a homage to the so-called Leonardo da Vinci Polyhedron, illustrated in Luca Pacioli’s Divina Proportione (Venice 1506). Fenhann shares the Renaissance artist’s fascination of geometrical beauty but this may also be a clue to a deeper understanding of his work. By proposing a dialogue between the mind, the hand and inventive technologies, thereby minimizing the boundaries between arts, crafts and science, Fenhann’s work is interdisciplinary in a way that does not seem far from a Leonardo da Vinci state of mind. Fenhann’s art is technically rich in the Greek sense of the word “techne”, often translated as craftsmanship or art, and it is actually related to the word “tekton”, meaning carpenter. The underlying idea is that wood is a raw material that the artist, or technician, shapes, thereby forcing the form to manifest itself. The Latin equivalent to “techne” is “ars”, and that term’s primary meaning is know-how, skill or artfulness.

The words technique, craftsmanship and art are etymologically closely connected and inconceivable without each other, because they proceed from the same existential attitude towards the world. But as the Czech-born philosopher Vilèm Flusser (1920-1991) has reminded us in his book “Von Stand Der Dinge. Eine Kleine Philosophie des Designs”, this bond was broken by modern bourgeois culture and its radical separation between fine arts and the world of technique and machines, which divided our culture into two radically separated domains: The “hard” quantifiable field of science and the “soft” qualitative faculty of the arts. However, as Flusser has pointed out, design has the great ability to “creating a bridge between the two because it embodies the intimate relationship between technology and art … leading the way towards a new culture.” This is what the Bauhaus-school did so masterfully, and also today, similar tendencies of interdisciplinary activities are becoming manifest. Fenhann’s design must be seen in this light. Through the timeless language of pure geometry, he contributes to the reconciliation of technique and art, tradition and innovation, and opens up new perspectives towards a synthesis between art, craft and the machine.

Hikari Icosa

2015

Black lacquered Oregon pine, Shoji paper

49 x 49 x 41,5 (h) cm

Limited edition of 8 + 2 AP

Handmade by the artist

Creating designs with an equal focus on sculptural and functional qualities, Rasmus Fenhann’s works are made in carefully selected natural materials, especially wood. He is considered as one of the most important Scandinavian designers today in the field of handmade art design. His working processes combines traditional, sometimes near-forgotten craft techniques with advanced high-tech procedures, including computer-based sketching and visualization. His painstakingly precise treatment of wood sur faces, ending up in a velvet-like, soft finish and with invisible joints, is the result of an extraordinary effort, which is both mental and physical. It is exquisite craftsmanship, close to the obsessive. In the words of the artist, “It has to do with being able to zoom in, infinitely… There mustn’t be any flaws, not even the tiniest, in the delicate woodwork. Time is key, and infinite repetition is expected until a level of breathtaking per fection is reached.”

Rasmus Fenhann has a double education from the Danish Royal Academy of Ar t and Design, Furniture Depar tment 1997-2003, and as a Cabinetmaker 1991-1996. He has frequently exhibited in Japan, Europe and in the United States, and his works are part of impor tant private and public collections including the permanent collection of the Designmuseum Danmark, Copenhagen, Denmark. Rasmus Fenhann has received several Prizes and awards such as the Danish Arts and Crafts Silver Medal, 2004; the Finn Juhl Prize, 2016 and most recently, the Inga & Ejvind Kold Christensen Prize in 2022.